Computer dust cleaning explained – what it is and why it matters

In repair work, a lot of “overheating” and “the fan won’t shut up” jobs start with dust, not a failed part. Computer dust is not anything special. It is the same stuff you see on shelves – household dust, fabric fibres, pet hair, and sometimes a sticky film from smoke or cooking. It gets pulled inside because computers move air through them to stay cool, and that airflow acts like a little vacuum cleaner over time. This article explains what dust does inside a computer, why it affects airflow, temperatures and noise, and why cleaning is about reliability rather than looks. It is not a tools list, and it is not a DIY guide. No thermal paste talk yet.

What “dust” inside a computer actually looks like

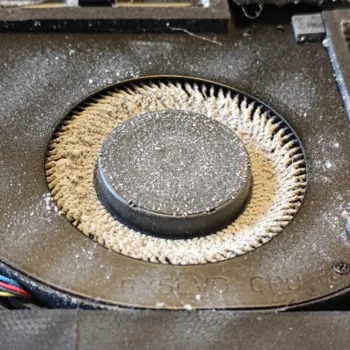

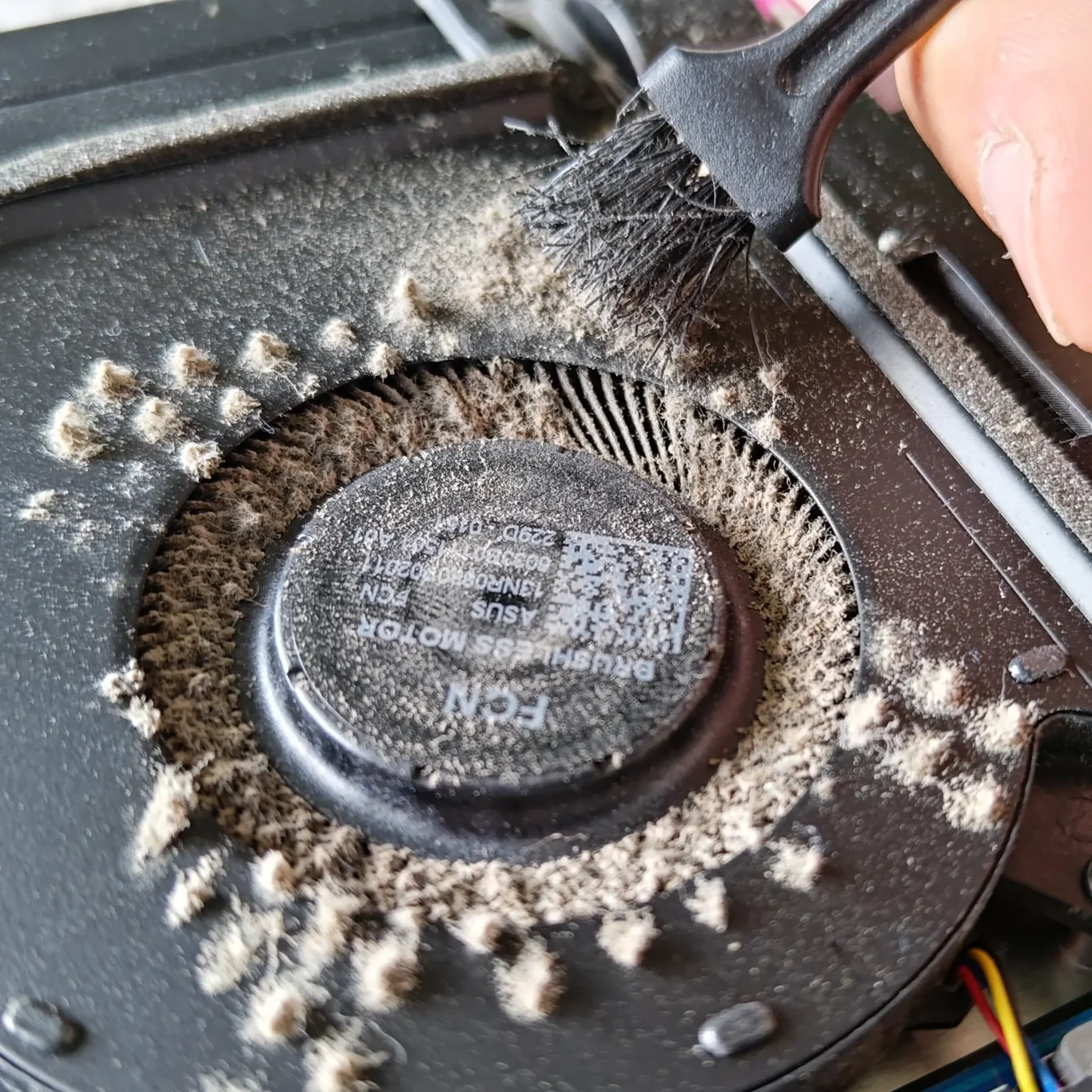

It is usually a compacted mix that builds up in specific places, not just a light film on parts.

When people picture dust inside a computer, they often imagine a thin grey coating. In reality it is usually a mix of fibres, hair, skin flakes, fabric lint, and general grime that gets carried in by airflow. Computers move air through the case to control temperature, so whatever is in that air slowly ends up inside the machine.

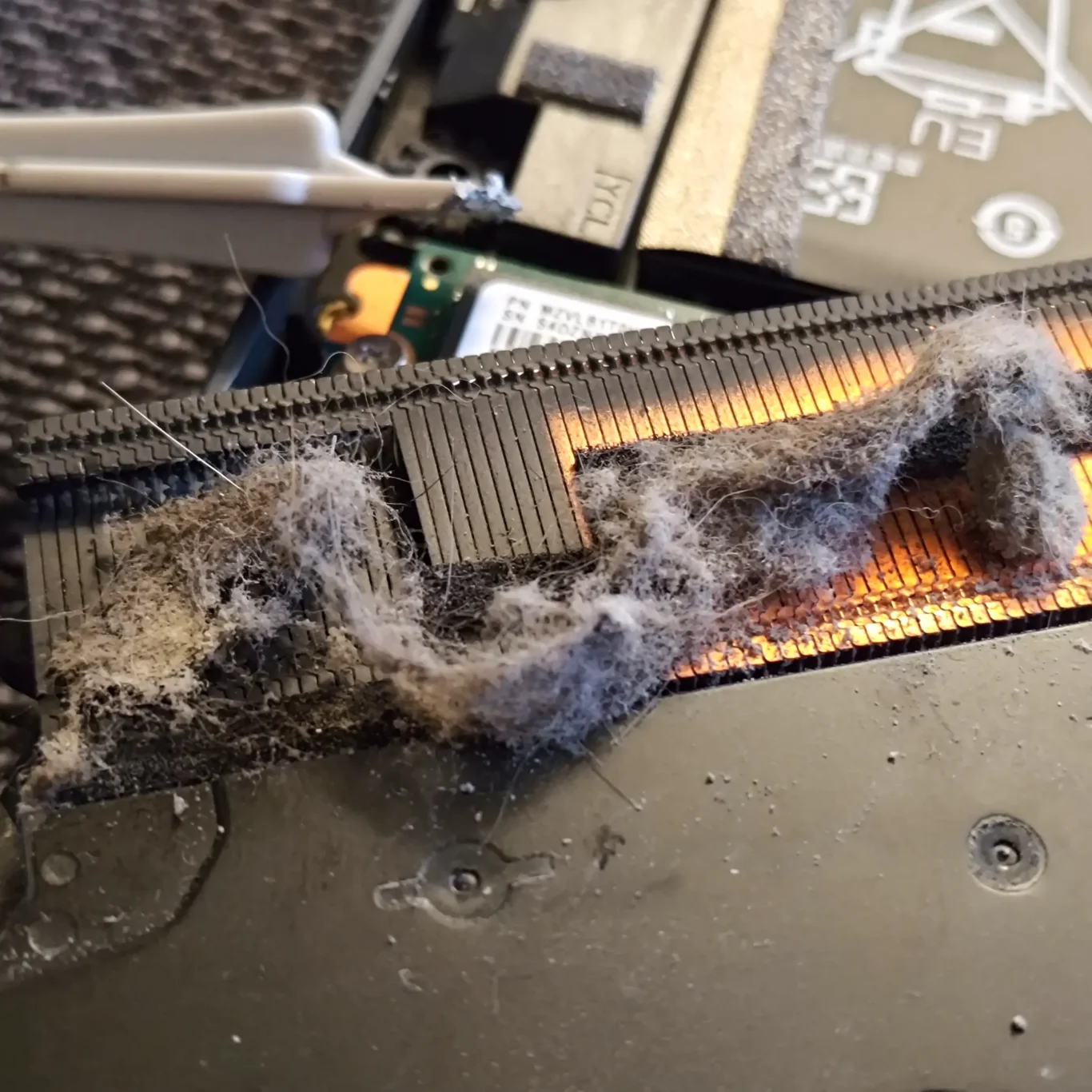

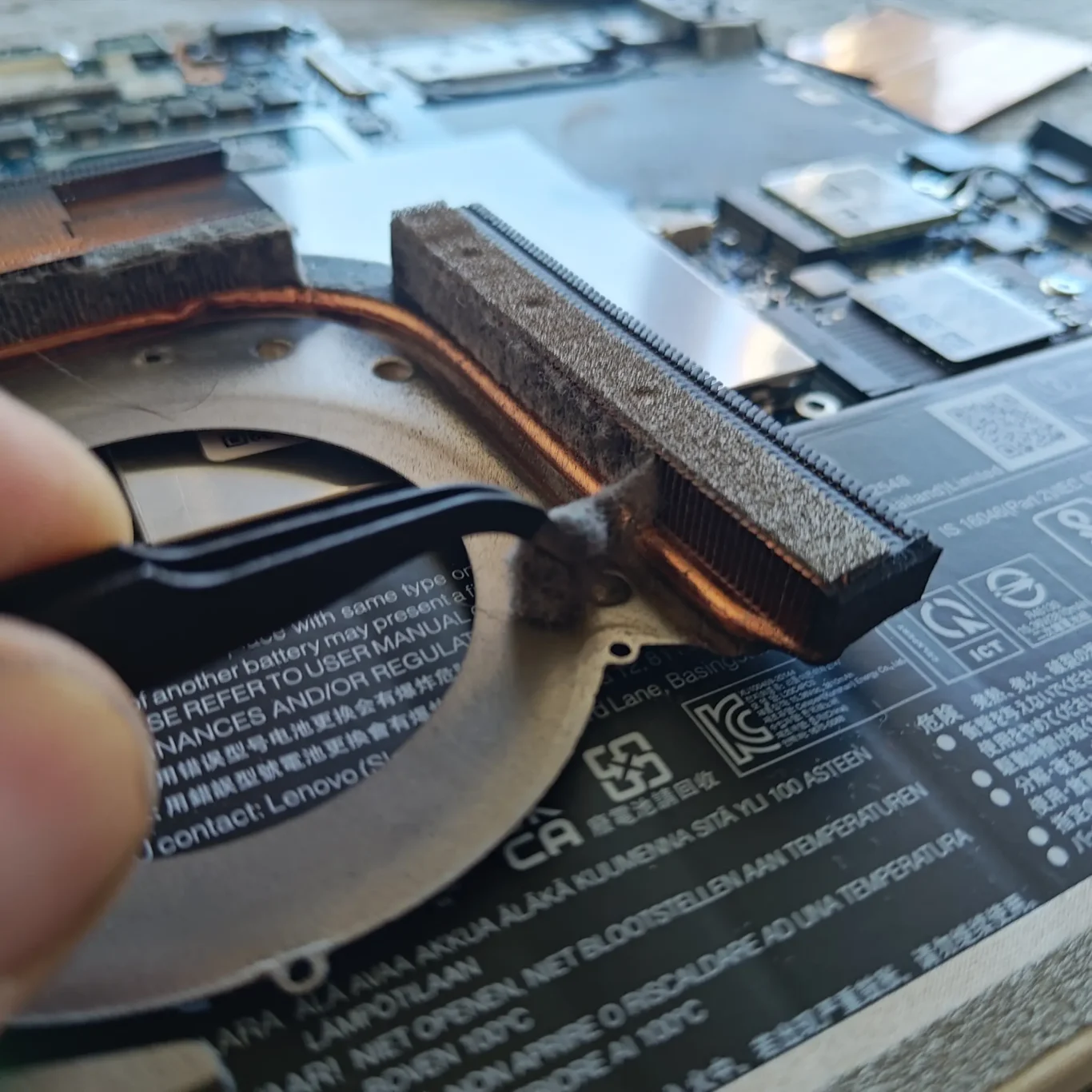

Over time, that loose dust does not stay loose. It collects where the air speed changes and where there are obstacles. It can build into mats and felt-like blocks around vents and heatsinks. A heatsink is the metal fins used to dump heat into the air. Those fins are great at catching dust, and once a few fibres get lodged, they trap more.

Sticky residues make this worse. If a machine lives near a kitchen, or in a space with smoking or vaping, a thin film can settle on surfaces. Dust then clings to it instead of blowing through, so clogs form faster and the buildup tends to be denser. In practice, these are the computers that come in with the loudest fans even when the hardware itself is fine.

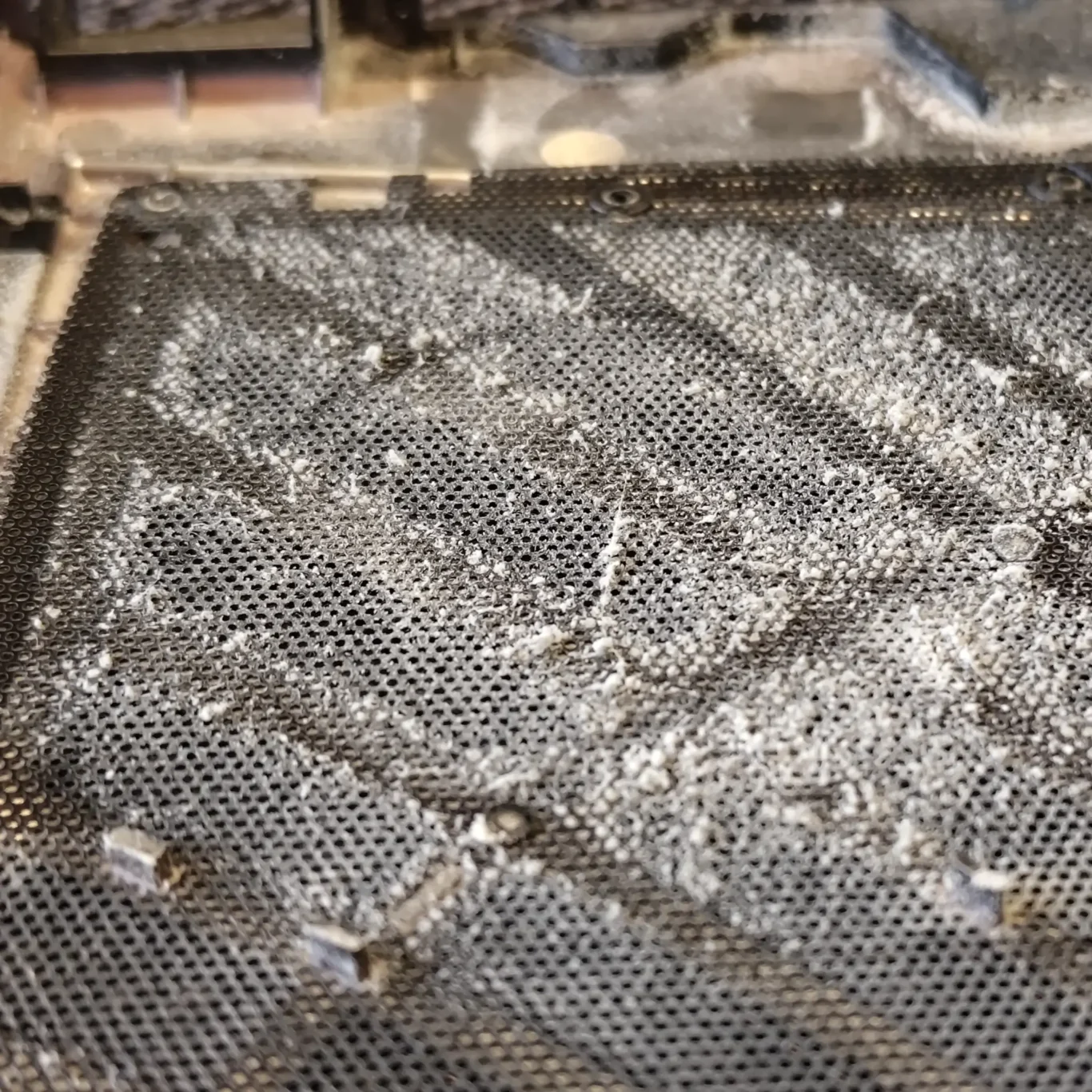

The common accumulation points are predictable. Intake areas pick up the first layer as air is pulled in. Fan blades collect a coating that can throw airflow off and add noise. Heatsink fins trap the worst of it because the gaps are narrow. Exhaust grills also clog, which matters because that is the air exit point.

A useful judgement call: if you can see a fuzzy line along vents or grills, it is rarely “just cosmetic”. It usually means there is more of the same on the inside, in the places you cannot see, and those are the places that affect cooling.

Why dust builds up in the first place (airflow basics without the jargon)

Moving air keeps components cool, but it also carries whatever is floating around the room and drops it where the air path narrows or changes direction.

Computers generate heat all the time. The processor, graphics chip, power parts, and even storage produce warmth when they are working. To stop that heat building up, fans pull air through the case or chassis and push warm air back out again.

That airflow is the whole point of the cooling system, but it has a side effect. Air is never perfectly clean. It carries fine dust, fabric fibres, skin flakes, pet hair, and sometimes greasy particles from cooking or smoke. If the machine is moving air, it is also moving those particles.

Every intake becomes a collection point for airborne debris. An intake is simply where air enters the computer, whether that is a grill, a gap in the chassis, or a vent on the underside of a laptop. The fan creates a pressure difference and the easiest path for air becomes the path for dust too.

Dust does not deposit evenly. It tends to settle where airflow gets messy. Turbulence at grills and tight fins encourages deposits because the air swirls and slows down, and particles stop travelling in a straight line. Those fins are part of the heatsink, the thin metal vanes that dump heat into the air. They also act like a very effective comb for fibres.

This is also why a computer can look clean on the outside and still be clogged inside. A vent might only show a light film, while the heatsink behind it has a dense mat that blocks the gaps where air should pass.

You will sometimes hear people talk about positive vs negative pressure. Positive pressure means the case is set up to push slightly more air in than it pulls out, so air tends to escape through gaps. Negative pressure is the opposite, where the system pulls more air out and replacement air gets sucked in through gaps. That is a high-level way of describing how air chooses its routes through a case.

Neither approach is dust-proof. With positive pressure, dust still enters through the intakes because air still enters through the intakes. With negative pressure, you can end up drawing air through unfiltered gaps, which also carries dust. In real repair work, I see dusty systems from both, because the room environment and runtime matter more than the theory.

A practical judgement call: if a machine runs long hours in a busy office, near fabric, or around food prep, assume dust build-up is part of normal maintenance, not an unusual fault. The cooling system is effectively acting like an air filter, even if it was never designed to be one.

How dust affects cooling: restricted airflow and insulated heatsinks

Dust causes overheating because it stops air moving through the places that are meant to shed heat

Cooling is basically two jobs. Move air where it needs to go, and let hot parts pass their heat into that moving air. Dust interferes with both, which is why cleaning is not cosmetic.

First, dust reduces airflow. Fans can only push so much air through a restricted path, and dust makes that path narrower. Less air moving through means less heat carried away. The fan may spin faster to compensate, but it still cannot push air through a blockage properly.

The worst build-up tends to be at the heatsink fins. A heatsink is the metal radiator-like part that dumps heat into the airflow. Those fins are thin and closely spaced, so they clog easily. Once dust and fibres bridge the gaps, the heatsink stops behaving like a radiator and starts behaving like a wall.

There is also a quieter issue that gets missed. A thin film of dust on metal surfaces can act like insulation. Heat does not move into air as well when there is a layer of grime in the way. Clean metal-to-air contact matters, even when the system does not look “blocked”.

Most people do not notice this happening because it is gradual. The machine runs a bit warmer, so the fan runs a bit more often. You get used to the new normal. Then one day the workload is slightly heavier, the room is warmer, or the laptop is on a soft surface, and it tips over into obvious symptoms.

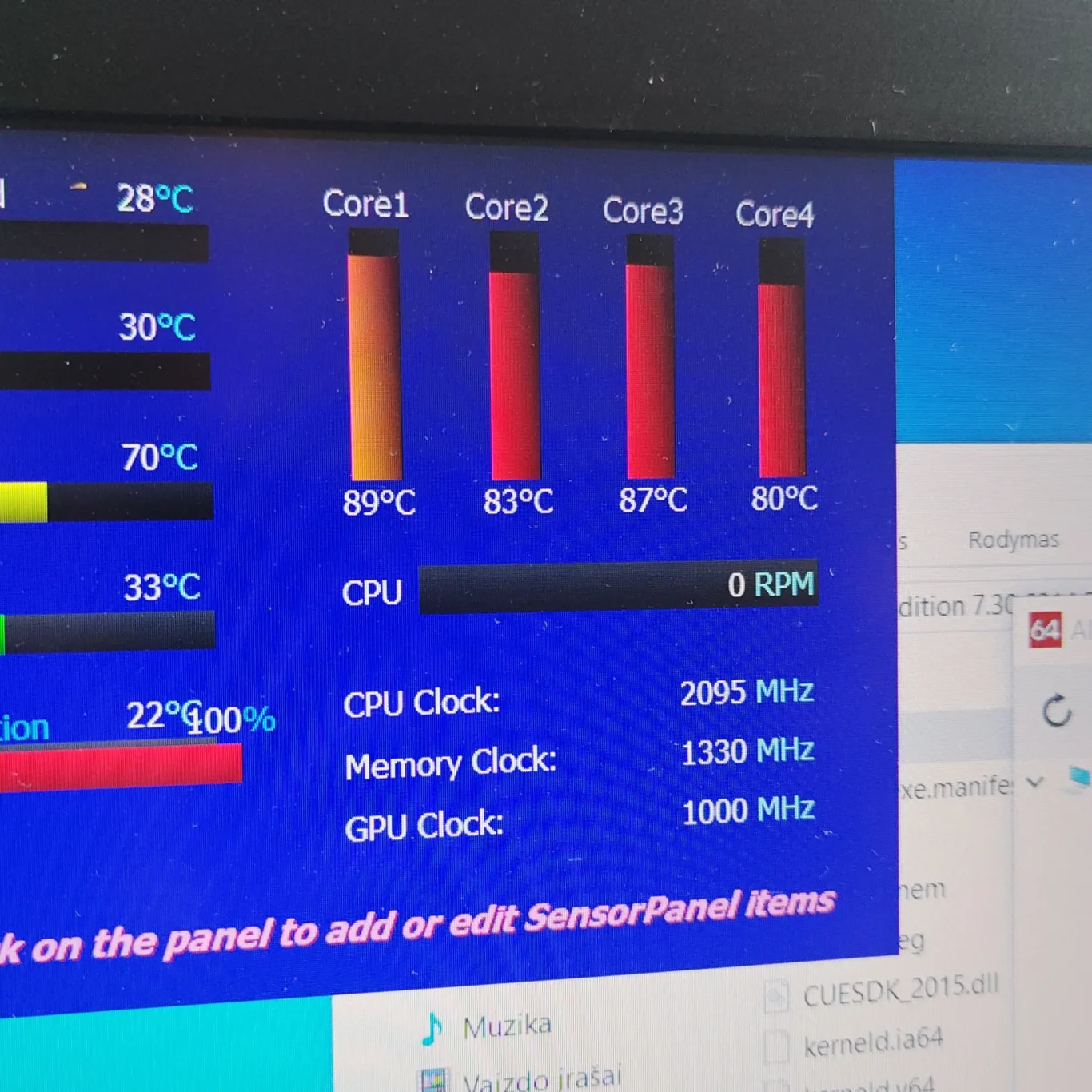

That is when you start seeing throttling or shutdowns. Throttling is when the computer slows itself down to reduce heat. It is a protection feature, not a fault by itself, but it is a clear sign the cooling system is not keeping up.

A practical judgement call: if the fan noise has crept up over months and the machine now feels hot doing the same everyday tasks, do not assume it is “just ageing”. Dust restriction is one of the first things worth checking because it affects everything else that relies on stable temperatures.

Noise: why dusty computers get loud

That “my fan is suddenly really noisy” moment is usually the cooling system working harder than it used to

Fan noise is one of the most common complaints I hear. People often assume something has snapped overnight. In reality, it is usually a gradual restriction that finally crosses a line where you notice it.

The main reason is simple. When dust reduces cooling, the system asks the fans to spin faster to compensate. Higher RPM means more noise, even if the fan itself is healthy. You might also notice the pitch change, not just the volume.

Dust does not only clog heatsinks. It also collects on the fan blades. That extra weight is rarely even, so the fan can become slightly unbalanced. When that happens you can get vibration through the chassis, or a faint buzzing that was not there before.

Restricted exhaust is another overlooked cause. If the air cannot leave cleanly, it gets forced through smaller gaps. That can create harsher airflow noise, like whistling, hissing, or a low roaring sound. It is the same fan speed, but the air path has turned rough.

Noise also comes and goes because the cooling system reacts to conditions. Workload matters. A video call, a big spreadsheet, or a browser with lots of tabs can push temperatures up enough to trigger a higher fan speed. Room temperature matters too, because the computer can only cool itself down to somewhere near the air it is taking in. A warmer office means the fans have to work harder for the same job.

A practical judgement call: if the machine is quiet when cold, then gets loud quickly under everyday tasks, treat it as a cooling capacity issue rather than “just a noisy fan”. It does not mean the fan is about to fail, but it does mean the system is having to compensate. Cleaning often helps, but it is not a promise of silence. Some laptops and small desktops are simply designed to run their fans audibly when they are under load.

Does dust affect performance? Sometimes, and usually in a predictable way

It tends to show up under steady pressure, not when you just open a few apps

Dust affects performance when it affects temperatures. Modern CPUs and GPUs protect themselves by reducing speed when they get too hot. This is called thermal throttling, and it is meant to stop damage.

In real use, throttling tends to appear first on sustained workloads. Things like gaming, long video calls, exporting files, compiling code, and large spreadsheets keep the processor or graphics chip working for minutes at a time. That steady load builds heat, and a dusty cooling system struggles to get rid of it.

Short bursts can feel completely normal. Opening email, launching a browser, or doing a quick edit might not last long enough for the heat to build. That is why people often miss the problem for months. The machine still feels “fine” until something keeps it busy.

When performance is affected, it is not always a constant slow-down. More often you see secondary effects: the fans get louder, the chassis warms up over time (heat soak), and you get occasional stutters. It might be a momentary dip in a meeting, a frame-rate wobble in a game, or a pause during an export, rather than the whole computer feeling slow all day.

A practical judgement call: if the computer is fast when cold but becomes noticeably worse after 10-20 minutes of the same task, think cooling first, not “the software is broken”. It does not prove dust is the only cause, but it is a common and predictable one, and it is worth ruling out before chasing more complicated fixes.

What happens if you never clean it

In the real world it usually gets gradually worse, and the symptoms stack up rather than arriving all at once.

Most computers do not go from “fine” to “dead” overnight just because of dust. What I see more often is a slow shift. The machine runs a bit warmer, then the fans start to work harder, then it becomes louder under the same everyday tasks. People notice it most on video calls, when driving an external monitor, or when they have lots of browser tabs open.

Overheating is usually progressive. Dust builds up on the heatsink fins and around the fan housing, so less air gets through. The system compensates by increasing fan speed. That means more noise, and it also means the fan is spending more of its life at the top end of its range. You might still get through the workday, but it feels less calm and less consistent.

If you keep leaving it, shutdowns become more likely under load, especially on laptops. This is a protective behaviour. When internal temperatures cross a limit, the computer can cut power to prevent damage. It often happens during something “normal” like a Teams call plus screen sharing, an export, or a big update in the background. Desktops can do it too, but laptops have tighter cooling and less spare airflow, so they hit the edge sooner.

Long term heat stress matters even when the machine does not shut down. High temperatures over months can age parts faster. Batteries tend to wear more quickly when they are kept hot. Fans can develop bearing wear from running hard and ingesting fine dust. Thermal pads can dry out and stop transferring heat properly. Some plastics and cable insulation can become more brittle when they spend years being heat soaked.

One important point: dust is usually a contributor, not the only cause. A failing fan, tired thermal paste, or blocked vents from the way the machine is used can overlap with dust build-up. Software load can be part of it too. A runaway background process, a heavy browser session, or a security scan can push temperatures up enough that a slightly compromised cooling system tips over into noisy or unstable behaviour. Thermal paste is the thin layer that helps heat move from the chip to the heatsink.

A practical judgement call: if the fans have become noticeably louder over a few months, or the machine is uncomfortable to use on your lap or desk, do not wait for a shutdown to “prove” there is a problem. It is usually cheaper and less disruptive to deal with cooling early, before heat starts to trigger instability or accelerate wear.

Why cleaning is not cosmetic

It is about keeping the cooling system working as designed, not making the case look nice

Inside a computer, dust is not just “mess”. It changes how the cooling system behaves. Fans, vents, and heatsinks are designed around clear air paths and a predictable flow of air. When those paths narrow or the fins get coated, the computer is no longer operating under the conditions it was built for.

A heatsink is the metal part that moves heat from the chip into the air. It relies on lots of thin fins and a steady stream of air between them. Dust acts like a blanket on those fins and it can also form a mat at the edge of the fan housing. The result is simple: less air through the heatsink, more heat left inside the machine.

This is why a “clean-looking” computer can still run hot. You can wipe the keyboard, the vents, and the outside panels and it still tells you nothing about what is sitting in the cooling channels. On many laptops the main dust build-up is behind the vents, not on them. On desktops it is often packed into the front intake filter, the CPU cooler fins, or the power supply intake where you cannot see it from a quick glance.

Proper internal dust cleaning targets function. Airflow comes first. Then heatsink efficiency. Then fan behaviour. If airflow is restricted, the fan has to spin faster to get the same cooling. That means more noise and more time spent at high RPM. Even if the computer does not feel “slow”, it can become less consistent because the system will reduce performance when temperatures rise. That is called thermal throttling, and it is the computer protecting itself.

From a repair bench point of view, cleaning is often the sensible first step when someone reports overheating or sudden fan noise. Not because it is the only possible cause, but because it is a common, testable variable that affects the whole thermal design. If you try to diagnose heat and noise complaints while leaving a blocked heatsink in place, you can end up chasing symptoms rather than causes.

A small judgement call that usually holds up: if a machine is stable when idle but gets loud or uncomfortable during routine work (video calls, browser-heavy days, external displays), start by checking the cooling path and dust load before assuming you need parts or software changes. It is basic maintenance, and it sets a clean baseline for any further diagnosis.

Laptop vs desktop: the same problem, different consequences

Dust causes overheating in both, but the design space and airflow routes change how quickly it shows up.

Laptops and desktops both rely on the same basic idea: move heat from the chips into the air, then get that warm air out of the case. Dust interferes with that flow. The difference is how much room each type of machine has to cope when the airflow starts to shrink.

In a laptop the cooling system is packed tight. You typically have a compact heatsink with very thin fins and smaller fans, so there is less margin for blockage. A little dust in the wrong place can reduce airflow a lot. When that happens, the fans ramp up early, noise becomes more noticeable, and temperatures rise faster under normal work.

Laptops also have a second issue that desktops usually avoid: vents can be blocked by soft surfaces. Beds, sofas, even some fabric laptop sleeves can restrict the intake or exhaust. Add dust on top of that and you get a double restriction. The machine then runs hotter for longer, which can lead to more thermal throttling. Thermal throttling is the system reducing speed to protect itself from heat.

Desktops have more airflow options. Larger cases can use bigger fans, wider vents, and more open heatsinks, so they can tolerate some dust before problems become obvious. But desktops collect dust steadily, and it tends to settle where the air is meant to enter. Front intakes and filters can get blanketed, and once that happens the whole case airflow suffers.

Desktop GPUs are worth a specific mention. A graphics card often has its own cooler and its own fin stack. If that clogs, you can end up with a noisy PC that still looks “fine” around the CPU area. Power supply intakes and CPU cooler fins can also pack up quietly, depending on the case layout.

All-in-ones and compact PCs sit in the middle. They are desktop-class internally, but they often have laptop-like constraints on space and airflow. That means dust can have laptop-style consequences, even though the machine is sitting on a desk.

A practical judgement call: if it is a laptop and the fan behaviour has changed noticeably, take it more seriously than you would on a roomy desktop tower. Laptops have less headroom, so small restrictions turn into heat and noise sooner. For a desktop, if you can see dust building on filters or front intakes, that is usually the best time to deal with it, before it starts affecting the GPU and the overall case temperature.

Common signs dust is now a problem (not just ‘a bit dirty’)

Use these symptoms as a quick checklist for when the cooling system is no longer coping normally.

Most computers get a bit dusty over time. That on its own is not a crisis. What matters is whether the dust is now interfering with airflow through the cooling system. When it does, the machine tends to tell you in fairly repeatable ways.

Fans running hard at idle or during light tasks. If the fan noise has become your new “background soundtrack” while you are just in email, a browser, or a spreadsheet, it often means the system is struggling to move heat out efficiently. Idle just means you are not asking much of the machine.

Hot palm rest, hot keyboard deck, or hot exhaust air soon after start-up. A bit of warm air is normal. Heat building quickly, especially within a few minutes of turning it on, is a sign the heat is not being carried away as easily as it should. On laptops you often feel this through the chassis before you see any obvious warning.

Unexpected slowdowns under load. Games that start stuttering, video calls that go choppy, or general “it was fine yesterday” sluggishness during busy work can be heat-related. Thermal throttling is when the system deliberately slows down to keep temperatures safe.

Sudden drops in performance during sustained work, or random shutdowns. If it runs normally for a while then abruptly slows, freezes, or powers off during longer tasks (exports, updates, long meetings, anything that keeps the CPU or GPU busy), treat that as a stability warning. It does not prove dust is the only cause, but overheating is one of the first things worth ruling out.

A musty smell or visible lint at the vents. You will not always get this. But if you can see lint packed at the exhaust or intake, or you notice a dusty, warm smell when the fan ramps up, it is a strong hint that the airflow path is getting restricted.

A small judgement call: if you have two or more of the symptoms above, and they are new or clearly getting worse, it is usually worth giving the cooling system attention sooner rather than later. Waiting rarely makes the noise or stability better, and it can make later diagnosis harder because the machine is not operating from a clean baseline.

Is cleaning really necessary? A practical way to think about it

Treat it as a risk question: will dust realistically start affecting cooling and stability in your setup?

Sometimes yes. Sometimes not yet. Laptop fan cleaning is not a “because it looks nicer” job. It is about keeping airflow open so the cooling system can move heat out properly.

It depends a lot on the environment the machine lives in. Homes with pets shed hair and fine dander that sticks to fan blades and grilles. Carpets tend to kick up fluff that settles in low intakes. Smoking leaves sticky residue that makes dust cling and mat together. Workshops add fine particles that pack into vents quickly. Kitchens are similar because grease in the air gives dust something to glue itself to. Even normal offices can be dusty, especially where paper, fabric chairs, and busy foot traffic are involved.

It also depends on how you use the computer. If it spends hours at high load, you will see the impact sooner. High load just means the CPU or graphics chip is working hard for long stretches, like video calls all day, exporting files, gaming, CAD, or running lots of browser tabs and apps at once. In those situations the fans run more, which pulls more air through the system, which also pulls more dust through it.

Design matters too. Some laptops run close to their thermal limit even when they are new. They are thin, the heatsinks are compact, and there is not much spare airflow. A small amount of blockage can turn into heat and noise fast. Desktops usually have more room and bigger fans, so they can tolerate some dust for longer, but they are not immune, especially if the front intakes and filters are clogged.

When might it not be urgent? If the machine is cool and quiet, behaviour is stable, and you use it lightly in a clean environment, it may be fine to leave it alone for now. “Stable” here means no new fan ramping, no heat you can feel through the chassis, no slowdowns under sustained work, and no odd shutdowns. In that situation, rushing to clean it is often unnecessary, and it can introduce risk if someone starts poking around without a reason.

A practical judgement call: if your computer is business-critical and you notice a clear change in fan noise or temperature, treat dust as something to rule out early. Not because dust is always the cause, but because it is one of the few common issues that can quietly lead to throttling (the system slowing itself down to stay safe) and knock-on reliability problems if you ignore it.

Cleaning as part of proper diagnosis (how repair shops look at it)

A sensible baseline check before anyone starts blaming costly parts

In a repair shop, dust cleaning is not treated as a cosmetic add-on. It is treated as part of checking the cooling system is actually able to do its job. If a machine is running hot, loud, or unstable, the first question is often simple: can air get in and out properly?

A technician will usually look for obvious blockage, the condition of the fan, and whether airflow is being choked off before assuming a CPU, graphics chip, or motherboard fault. That includes checking vents and filters, looking for a felt-like mat of dust on the heatsink, and listening for fan noise that suggests worn bearings. A fan bearing is the internal part that lets the fan spin smoothly.

This matters because cleaning can reveal other faults that dust was hiding. A fan might be failing even after the blockage is cleared. Heatsink fins can be bent or damaged, which reduces surface area and airflow. Mounts can be loose, which stops good contact between the cooler and the chip. Missing screws are common after previous work, and that can change pressure and airflow in ways that make temperatures unpredictable.

It is also worth separating two jobs that often get bundled together in people’s minds. Computer dust cleaning and thermal paste replacement are related, but they are not the same thing. Paste sits between the chip and heatsink to help heat transfer, while dust affects airflow through the cooler. A shop should decide which one is needed based on symptoms and inspection, not habit.

Good practice is to do only what the evidence supports. If the machine is clearly blocked and the fan is healthy, cleaning might be the right first step and may be enough. If the fan is noisy, wobbling, or not reaching speed, cleaning alone is unlikely to solve it, and it is better to address the fan rather than keep forcing it to work harder.

A practical judgement call: if you rely on the computer for work and you are chasing random slowdowns or shutdowns, it is reasonable to ask for cooling and airflow to be checked early. Not because it is always the answer, but because it is a safe baseline that can prevent misdiagnosis and helps any further testing make sense.

FAQ

Words from the experts

In the workshop we often see the same pattern: a machine that used to run quietly starts running hot, then the fan spends more time at higher speed because airflow is struggling. One practical detail we check is the load behaviour – whether the noise and heat ramp up quickly under sustained work or only at idle.

If your computer stays cool and quiet in normal use, cleaning is usually not urgent, but it is still sensible maintenance rather than something cosmetic. If it is getting louder, feeling hotter than it used to, or slowing down under load, dust becomes a likely contributor and it is worth treating it as a reliability issue, not just a bit of mess.